Ryan Krzykowski grew up in southwest Florida, an ideal place to grow up if you love sports. The weather is great pretty much year-round. Other than the occasional tropical storm, there’s little that can get in the way of playing sports outdoors.

Krzykowski played a lot of sports, but he got really good at football and baseball. It became his world.

“I was really obsessed and consumed by sports,” he said. “There’s some good that comes from that. But there’s also some not-so-good that comes with being consumed by anything. Sports was undoubtedly an idol in my life. Sports was definitely what I cared most about.

“My self-worth was based on how well I had played in my last game, or how confident I felt going into my next game. That was who I was.”

He knew he wasn’t good enough to be a pro athlete, but he wanted a career in sports. Before that though, he played college football at Yale for legendary coach Carm Cozza. Cozza coached at Yale for more than 30 years. The College Football Hall of Famer won 10 Ivy League championships. His last four years were Krzykowski’s four years.

But that’s not what Krzykowski remembers most.

“He was more concerned with what his players became as men than he was with their performance,” Krzykowski said. “He obviously wanted to win and knew that winning was essential to not only keeping his job but to pursuing excellence. Winning is a component of that.

“But at the end of the day, he was there to develop men. I heard those things when I was playing, but I don’t think I really grasped what that meant. Looking back, I have a much greater appreciation for a mindset like those types of ideals and for a career that was built upon them.”

When he graduated, Krzykowski became a coach, because he wanted to help young people develop their skills. He was focused primarily on what his players did on the field. He also started coaching his sons as they got old enough to compete.

His oldest, Robbie, was a pretty good baseball player at age 8, and he loved nothing more than playing sports, watching sports and reading about sports.

“As a young dad, that was cool. Every day, it was, ‘Dad, can you pitch to me? Dad, can you play catch with me?’ It really was about as good as it gets.”

It was while coaching Robbie, however, that Krzykowski realized that he needed to change his approach.

“We were playing catch one day and it dawned on me, my 8-year-old son was pretty good. He probably wasn’t the best kid his age, but he was pretty good. We’d put in a lot of hours and a lot of reps. I wondered how good he could be.

“Something flipped inside of me. I was no longer playing with my son and helping him to experience joy. I started coaching him and training him to maximize his athletic potential. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with having an athlete who wants to maximize his or her potential. But I managed to systematically suck the love that my son had for his favorite sport right out of him.

“The kid didn’t want to play baseball anymore, because I made it no fun. I turned it into work. I turned it into something with negative reinforcement over and over and over again. I thought I was helping him. And really all I did was make it no fun.”

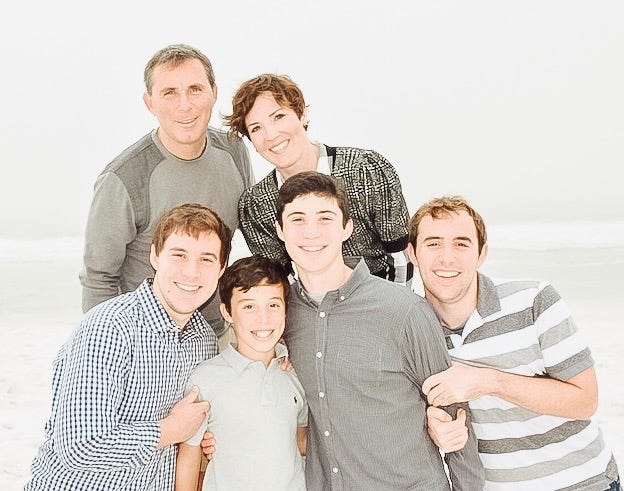

Through contact with former pro football player Joe Ehrmann, who wrote Inside Out Coaching, Krzykowski learned about coaching with a purpose. Krzykowski moved to the Kansas City area with his wife, Erica, and their four sons in 2008 to become the coaches ministry director in the Kansas City office of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

In 2012, he left the FCA staff and founded Community For Coaches (CFC), which uses sports to transform the lives of coaches, intentionally and effectively. CFC has a mentorship program that pairs young and old coaches so they can learn from each other.

CFC reminds coaches why they coach.

It’s not just about wins and losses; it’s about the journey. It doesn’t diminish the value of pursuing excellence, but it puts the wins and losses into perspective.

Hall of Fame basketball coach Dean Smith had a great philosophy about that. Smith won 879 games—the most among all college basketball coaches when he retired—but he also lost 254 times. He’s quoted as saying, “If you make every game a life-and-death thing, you’re going to have problems. You’ll be dead a lot.”

Sports can teach us so much that’s applicable to the rest of life. For example, Krzykowski says that “hard” and “bad” are not the same thing.

“When our athletes get to a certain age, they have the ability to understand that practicing hard and training hard pays off. It helps them learn about being resilient and selfless, which is built around the idea of competing joyfully. There is great satisfaction that comes from giving something everything you have.”

It’s hard to find joy when you’re getting thumped repeatedly. But you have to learn to enjoy the process of learning, or you won’t get better. It’s not an either/or, it’s both.

“By loving each other and holding each other accountable, you’ll push each other to get better,” Krzykowski said. “When I can help young people learn to really enjoy what they’re doing, when I can teach them to love the people around them and hold each other accountable, I’m doing my job.

“There’s no better way to get a team ready to win than to help them practice as hard as they can, and to train as hard as they can, and learn to love what they’re doing and to love the people around them. There’s nothing that’s more motivational for an athlete.

“The ball still may not bounce your way on any given day, but you’ll get the most out of your athletes and they’ll get the most out of their participation in sports.”

CFC believes there are absolutes in sports. First, a coach can have a huge impact on the athletes he or she coaches. Second, kids are precious gems that need to be refined. That process needs to be purposeful.

That is why they help coaches develop personal purpose statements. Krzykowski, who is an assistant football coach at Olathe (Kansas) West High School, shared his: “I coach to help athletes compete joyfully, and to guide them toward becoming resilient, selfless encouragers, who are known by their love for each other.”

CFC encourages coaches to think about why they coach with the end in mind. A purpose statement gives them something to shoot for.

Obviously, no one lives out their purpose statement perfectly, but having a purpose statement that you believe in can help you get back on track when you don’t.

CFC is now 13-years old, about the age of a young athlete when he or she discovers the role that sports can play in their future.

Through the years, CFC has been modified and refined, much as the organization encourages its coaches to do with their own purpose statements. It’s a process, one that has the end result in mind: to restore the joy of participating in sports, while keeping it in the proper perspective.

It just can’t be an obsession.